ERC Employment Testing Investigation Exposes Potential Discrimination at Staffing Agencies in Houston, TX and Nashville, TN

By: Elias Cohn

February 14, 2024

On a January morning in 2023, two men in their early 20s walked into the same staffing agency in Houston, TX, about 10 minutes apart from one another. Both men had already submitted applications to the agency a few days before, listing the same type and duration of work experience, the same level of education, and the same job preferences. Both men were dressed according to the same dress code and asked for the same type of work. An employee at the agency told one man that there were no jobs available, but told the other man about a job unloading trucks in downtown Houston, and then called him two days later to offer him the job. Why were these two equally qualified job applicants treated differently? According to a recent report by the Action Center on Race & the Economy (ACRE), based in part on the ERC’s employment investigations, the difference could have been their race.

The men in the scenario I just described were not actual job applicants, but “testers” participating in an ERC investigation to determine whether staffing agencies across Houston, TX, and Nashville, TN, were complying with civil rights employment laws. On December 12, 2023, ACRE released Untangling Discrimination, a comprehensive report based on the results of this investigation, which revealed potential racial discrimination and job segregation at staffing agencies in both cities, as well as potential gender-based discrimination and job segregation at staffing agencies in Houston.

The Staffing Industry

Staffing agencies (sometimes called “temp agencies” or “employment agencies”) form a $186 billion industry and employ approximately 14.5 million people in the U.S. each year according to the American Staffing Association.[1] Employers who use staffing agencies to recruit workers for industrial warehouse and factory positions claim that these companies provide a flexible labor model which benefits both employees and employers. But workers, labor advocates, and government regulators, have documented serious misconduct at some staffing agencies, including discrimination, wage theft, and subjecting workers to poor and/or dangerous working conditions.[2] Moreover, labor advocates allege that some corporations now outsource hiring to these independent companies to shield themselves from responsibility for labor violations and to undermine workers’ efforts to unionize and negotiate for more rights. Advocates accuse employers and staffing agencies of working together to create an underclass of “perma-temp” laborers who often remain in “temporary” positions for years without the stability and benefits of permanent “direct-hire” employment.[3]

Anecdotal evidence, journalistic investigations, and previous lawsuits suggest that hiring discrimination is rampant at some staffing agencies, but this form of mistreatment is often difficult to document and prove.[4] For this reason, Grassroots Law and Organizing for Workers (GLOW), a national legal advocacy group, hired the ERC to investigate a list of staffing agencies in both Nashville and Houston to see whether their hiring practices were discriminatory.

Matched-Pair Civil Rights Testing

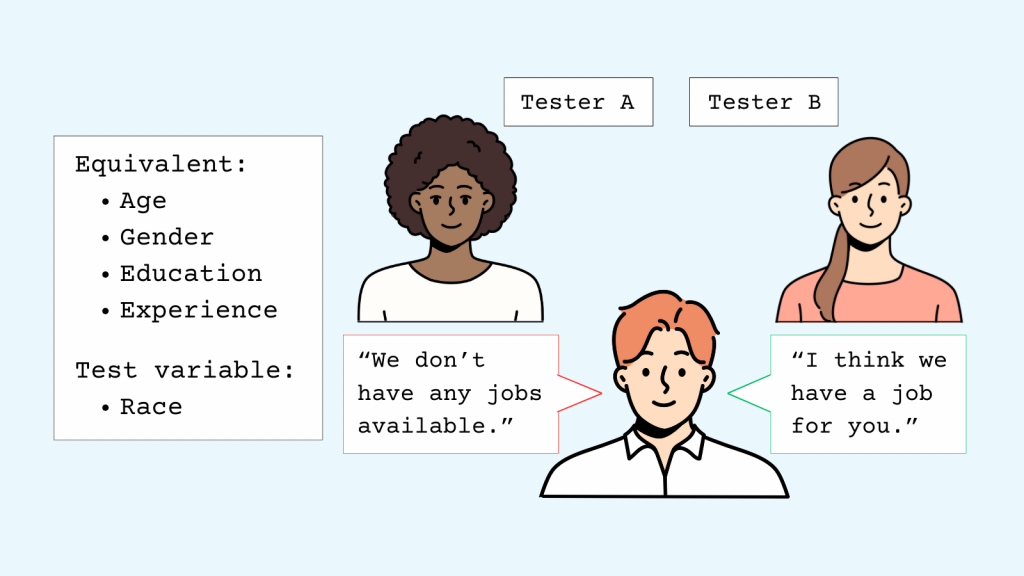

The ERC employed an investigative method called matched-pair civil rights testing to objectively determine whether these agencies were discriminating based on race and/or gender when hiring new job applicants. Matched-pair testing has been used for decades to detect discrimination in housing, public accommodations, government services, accessibility, and employment. The method compares treatment between two applicants based on one variable—such as race or gender—by controlling for all the other differences between the two applicants.

In simpler terms, the ERC’s sent pairs of people—called “testers”—into each agency to apply for jobs. Each pair consisted of two individuals who entered the agency within approximately 15 minutes of one another. In race tests, the ERC paired a Black tester with a Latino or Latina tester of the same gender. In gender tests, the ERC paired a Black man with a Black woman, or a Latino with a Latina. The ERC carefully trained each tester to provide substantially similar job qualifications and job preferences as their paired “test partner” when they applied. Each tester documented the treatment they received by covertly making an audio recording of their time in the agency and immediately filing a report detailing their interactions with agency employees. The ERC then carefully analyzed these reports and audio recordings to see whether agencies treated the two testers within a pair differently from one another.

ERC’s Investigative Findings

ERC’s Investigative Findings

As detailed in ACRE’s report, in Houston the ERC found potential race-based discrimination and/or segregation at five out of the ten agencies it tested and found potential gender-based discrimination and/or segregation at nine out of 11 agencies it tested. In Nashville, the ERC found potential race-based discrimination and/or segregation at three of the ten agencies it tested. The ERC did not test for gender-based discrimination in Nashville.

In some of these cases, agencies appeared to discriminate against Black or female job applicants. For example:

- During a race-based test, a Black woman and a Latina entered the same agency within approximately 15 minutes of one another. They each said they were looking for work and provided substantially similar job qualifications and preferences, but the agency offered the Latina tester an interview for a warehouse packaging position at $15/hour and did not offer the Black tester any information about available positions. The agency then called the Latina tester five times within two days of her initial visit. They did not contact the Black tester until one month after the initial visit, when they left a voicemail asking her to call back.

- During a gender-based test, a Latina and a Latino tester entered the same agency within about 15 minutes of one another. The agency told the male tester about a job loading and unloading trailers for $14/hour, but only told the female tester about a potential future job on a newspaper production line that was not yet hiring. The agency followed up with the male tester confirming availability of the job but sent the female tester an email saying no jobs were available that fit her qualifications.

The ERC also found instances in which agencies appeared to segregate job offers by race or gender, though it was difficult to say which tester received better treatment. For example:

- A Black tester and Latino tester entered an agency within approximately 15 minutes of one another. The agency provided information to the Black tester about a job that paid $13/hour and provided information to the Latino tester about a job that paid $15/hour. But the job they offered to the Latino tester involved heavy lifting and standing for long periods of time as well as the use of a back brace he would need to purchase at his own expense. The agency contacted the Black tester after the initial visit to follow-up and did not follow-up with the Latino tester.

- In a case like this it may be difficult to say which tester received better treatment or better opportunities. But it seems that the agency offered the two testers different opportunities at separate job sites, though the testers provided the same qualifications and preferences. This type of practice may contribute to segregated job sites, and in this case, may have deprived both job applicants of the opportunity to choose between the higher paying job and the job that appeared to be less physically demanding.

The ERC investigation also captured vivid examples of agency employees treating Black testers and female testers differently on an interpersonal level during the application process. For example:

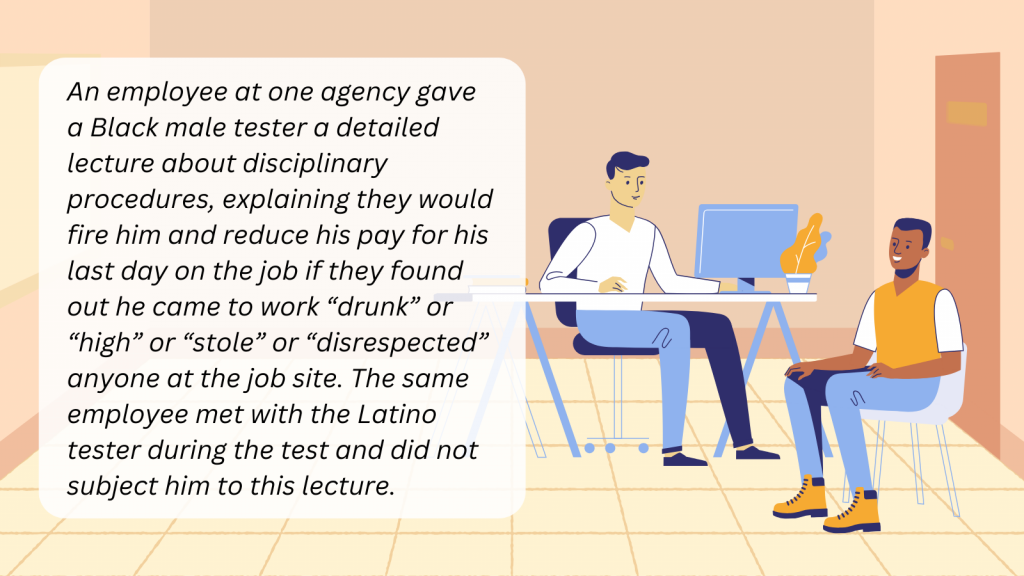

- An employee at one agency gave a Black male tester a detailed lecture about disciplinary procedures, explaining they would fire him and reduce his pay for his last day on the job if they found out he came to work “drunk” or “high” or “stole” or “disrespected” anyone at the job site. The same employee met with the Latino tester during the test and did not subject him to this lecture.

- In another test, a male employee appeared to “hit on” a female tester, saying he gave her a job because he, as he said, “I like you or something… you got a smile or something.”

Impact

Impact

Though temp workers and advocates have complained for decades about discriminatory treatment at staffing agencies, an applicant who received the treatment outlined in these tests might have no way of knowing—let alone proving—that an agency discriminated against them. That’s why matched-pair testing is so important. Through the investigation, the ERC has illuminated how these agencies operate, by showing that two job applicants of different races or genders may enter an agency at the same time, present similar qualifications and preferences, and still receive substantially different treatment. The ERC’s testing documents specific, verifiable examples of what discriminatory hiring practices at these agencies may look and sound like and who may be participating in the mistreatment of temp workers.

ACRE’s full report, Untangling Discrimination, is available here.

Endnotes:

[1] “Staffing Industry Statistics,” American Staffing Association.

[2] “Low Wage, High Violation Industries,” Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), last accessed Aug. 24, 2023. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ whd/data/charts/low-wage-high-violation-industries.

[3] Flanagan, Jane. “Fissured opportunity: How staffing agencies stifle labor market competition and keep workers temp.” Journal of Law and Society 20:2 (2020), 258. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A639809660/AONE?u=anon~3446467c&sid=googleScholar&xid=d787c6ce.

[4] Evans, Will. “When companies hire temp workers by race, black applicants lose out” Reveal News. January 6, 2016. https://revealnews.org/article/when-companies-hire-temp-workers-by-race-black-applicants-lose-out/.

———

The ERC is a civil rights organization that identifies and seeks to eliminate unlawful and unfair discrimination in housing, employment and public accommodations in its home community of Greater Washington DC and nationwide. The ERC’s core strategy for identifying unlawful and unfair discrimination is civil rights testing. When the ERC identifies discrimination, it seeks to eliminate it through the use of testing data to educate the public and business community, support policy advocacy, conduct compliance testing and training, and, if necessary, take enforcement action. For more information, please visit www.equalrightscenter.org