Environmental Justice Is a Key Component of Fair Housing

By Anika Rao-Mruthyunjaya, Nick Adjami, and Hana Cho

November 19, 2024

A third of Washington, D.C. is served by a combined sewer system in which sewage and storm water pass through the same pipes. These parts of the city are vulnerable to flash flooding, as heavy rainfall can overwhelm the system. Flash flooding can cause serious property damage and pose health and safety concerns to residents. In D.C., more than 90 percent of single-family homes located in flood hazard zones are in Wards 7 and 8, where over 90 percent of residents are Black and the median household income is less than half the citywide median household income.

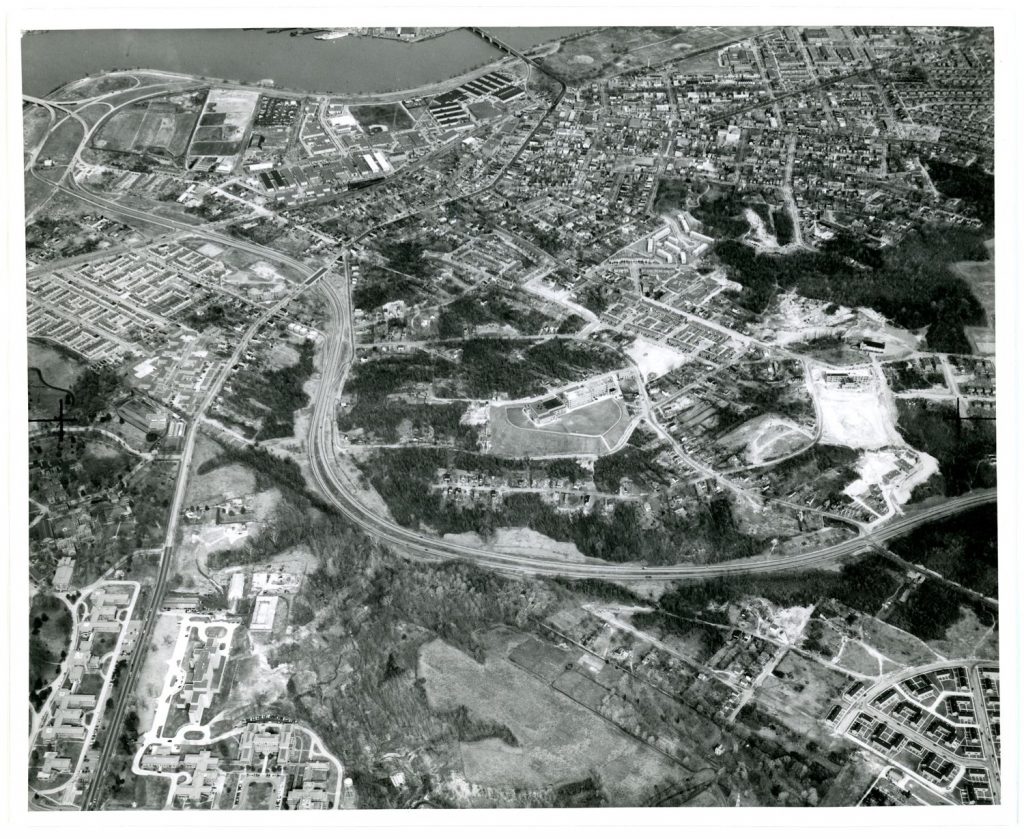

The fact that low-income Black residents are most vulnerable to flooding is not a coincidence, but the result of historical and ongoing segregation and racist housing policy. For example, the construction of Suitland Parkway and Interstate 295 cut through majority-Black neighborhoods like Hillsdale, displacing residents and increasing pollution. Crucially, those projects also removed vegetation that had served to absorb water during heavy rains. As a result, the highway forced stormwater into communities of color without appropriate stormwater infrastructure. This is one example of what has become known as Environmental Racism.

Aerial view of the Suitland Parkway in Southeast D.C. in 1955. Credit: DC History Center, Whetzel Aerial Photograph Collection, AE0042.

What Is Environmental Racism?

Environmental Racism is a systemic form of racism whereby communities of color are disproportionately exposed to and harmed by adverse environmental factors, such as air pollution, water contamination, flooding, and extreme heat.

Even environmental hazards like natural disasters that might seem non-discriminatory often disproportionately harm communities of color. This is because racism has been built into the fabric of many American cities through historical practices like redlining and disinvestment, which made communities of color more vulnerable to future harms. Racism can also play into disaster relief programs, further disadvantaging those communities.

What Is Environmental Justice?

Environmental Justice is a framework for remedying and eradicating Environmental Racism. The framework strives to ensure that all individuals, regardless of income, race, national origin, disability, or other identities, are treated justly and involved meaningfully in decision-making related to the environment and their health. Environmental Justice recognizes that certain communities have experienced direct harm due to systemic oppression. It strives to address these harms, protect people from unequal, adverse health and environmental risks, and ensure everyone has access to a healthy and sustainable environment.

How Is Environmental Justice Related to Fair Housing?

Fair Housing refers to a person’s ability to access housing in their neighborhood of choice, free from discrimination and segregation. The Fair Housing Act is a federal law which protects people from discrimination in housing-related activities based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex (including sexual orientation and gender identity), disability, and familial status. Before the Fair Housing Act, restrictive laws forced people of color into less desirable neighborhoods, segregated from white communities. Segregation was entrenched by federal policies and practices like redlining.

In the 1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation created maps ranking the “creditworthiness” of properties within American cities, but its metrics were heavily based on each neighborhood’s racial composition. Communities of color were deemed bad investments, prompting lending institutions to deny residents access to capital investment, which could have improved their housing and economic opportunities.

These policies created a self-fulfilling prophecy, trapping many communities of color in patterns of disadvantage and neglect. Those disadvantages were often compounded by environmental factors. Government officials and corporations seeking to build infrastructure like highways, factories, and petrochemical plants often did so in low-income communities of color. They viewed these communities as the “path of least resistance,” and felt comfortable sacrificing them for economic gain. These projects inevitably brought pollution, flooding, and other hazards into the neighborhoods, often in close proximity to homes, schools, and parks. In D.C., for example, toxic environmental factors in Wards 7 and 8 cause residents to develop asthma at much higher rates than people who live in other parts of the city. In short, one’s access (or lack of access) to a healthy environment is directly connected to historical and ongoing housing and land use policies.

Making Environmental Justice a Reality

Disproportionate, negative environmental outcomes and impacts in communities of color are not a foregone conclusion. Despite the odds stacked against them, marginalized communities have long fought back against racist policymaking. In fact, environmental justice activists in Chicago recently won a big victory that could help inform similar efforts nationwide.

In the 1970s, General Iron Industries opened a car-shredding facility on Chicago’s North Side near Lincoln Park. In addition to small pieces of metal, the plant produced black dust, foul odors, and loud noises. Since 2001, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) cited the shredder twice for clean air violations. Residents of the wealthy, majority-white neighborhood that grew to abut the plant complained, and in 2018, General Iron decided to make a change. But they did not announce any new tools to control emissions. Rather, they decided simply to move the plant to Chicago’s Southeast Side, a majority Latino neighborhood, claiming support from city officials.

General Iron Industries Inc. by Patrick Houdek, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

General Iron’s decision sparked significant backlash. Residents organized demonstrations, die-ins, and hunger strikes in protest. Three Southeast Side environmental justice organizations also filed a civil rights complaint with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), prompting an investigation. The investigation found that the city “discriminates against its residents by helping arrange for polluting businesses to move to low-income communities of color such as the Southeast Side sometimes from wealthier, heavily white communities including Lincoln Park.” In 2023, HUD reached a settlement with the city and those three Southeast Side environmental justice organizations to overhaul the city’s discriminatory zoning and land use policies.

The settlement required Chicago to conduct a formal assessment of neighborhoods’ environmental burdens and use those findings to craft reforms. Additionally, future planning and zoning decisions will be overseen by an environmental justice project manager and must consider potential pollution to overburdened communities. Southeast Side residents are hopeful that these changes will protect their neighborhood from increased pollution and that the city will make more equitable decisions going forward.

Environmental justice and fair housing are intertwined: neither can be achieved without the other. While racism and segregation have limited the ability of communities of color to access a healthy environment, strong fair housing and environmental justice movements are working to right those entrenched wrongs. In D.C., Chicago, and across the country, activists are turning the tide toward a cleaner, healthier future for all.

———

The Equal Rights Center (ERC) — a national non-profit organization — is a civil rights organization that identifies and seeks to eliminate unlawful and unfair discrimination in housing, employment and public accommodations in its home community of Greater Washington DC and nationwide. The ERC’s core strategy for identifying unlawful and unfair discrimination is civil rights testing. When the ERC identifies discrimination, it seeks to eliminate it through the use of testing data to educate the public and business community, support policy advocacy, conduct compliance testing and training, and, if necessary, take enforcement action. For more information, please visit www.equalrightscenter.org.

The work that provided the basis for this publication was supported by funding under a grant with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The substance and findings of the work are dedicated to the public. The author and publisher are solely responsible for the accuracy of the statements and interpretations contained in this publication. Such interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Government.