Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing: Proposed Rule Fails to Address Discrimination and Segregation

By Nick Adjami

March 10, 2020

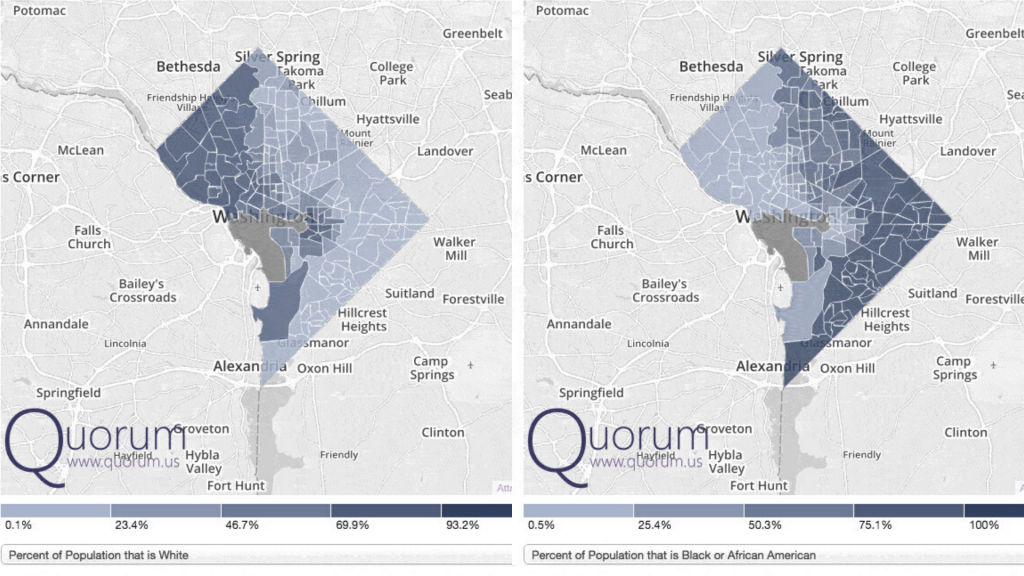

In the Equal Rights Center’s home community of Washington, DC, residential segregation is readily apparent. The city’s white residents reside predominantly in the Northwest quadrant, while its Black residents reside mainly in the Northeast and Southeast. Demographic maps of the city, shown below, provide a particularly stark visual representation of the situation.

Where a person lives has wide-reaching implications. It determines one’s access to resources and life outcomes like educational achievement and life expectancy. In DC, those who live East of the Anacostia River have less access to public transit, have more difficulty accessing healthy food, are more likely to develop asthma, and are more likely to be exposed to violent crime.

DC’s geographic racial divide and corresponding disparities did not happen by chance but are the result of a long history of discrimination against the city’s Black residents. DC is not alone in this. Nationwide policies like redlining, whereby communities of color were marked as “hazardous” for investment and cut off from access to credit, and practices such as racially restrictive covenants, which barred people of color from living in certain properties or neighborhoods, isolated Black Americans from opportunity. These systems entrenched geographic and socio-economic racial gaps that still persist today.

The passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 made it illegal to discriminate in housing on the basis of race, color, national origin, or religion. As such, it banned redlining and made the enforcement of racially restrictive covenants illegal. However, the FHA did not stop at outlawing housing discrimination. The FHA’s authors recognized the harm that had been done, and the work required to undo that harm, and so included an “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing” (AFFH) provision. The AFFH provision requires that “all executive departments and agencies” including the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and HUD programs proactively promote fair housing and integration.

Unfortunately, over fifty years later, we as a nation have made little progress toward this goal. Segregation persists, not just in DC as evident in the maps above, but in metropolitan areas across the nation. Partially, this is due to a lack of meaningful regulations and oversight guiding HUD program participants and jurisdictions in their duty to affirmatively further fair housing. But, in 2015 some progress was made. The Obama administration issued a rule that re-asserted HUD’s responsibility to the AFFH mandate, defined exactly what it means to “affirmatively further fair housing,” and implemented a system to achieve that goal. Per the 2015 rule, “Affirmatively furthering fair housing means taking meaningful actions, in addition to combating discrimination, that overcome patterns of segregation and foster inclusive communities free from barriers that restrict access to opportunity based on protected characteristics.” The rule envisions a society in which segregation is replaced with “truly integrated and balanced living patterns,” and “racially and ethnically concentrated areas of poverty” are transformed into “areas of opportunity.”

The rule also provided clear guidance to program participants and jurisdictions on their role in advancing fair housing choice and integration. Compared to the previous system, this new rule focused more on accountability and results. It introduced the “Assessment of Fair Housing” (AFH) tool, which provided program participants with a standardized framework by which to examine and challenge fair housing issues. Under the rule, HUD also promised to provide pertinent data to local jurisdictions for them to use in their assessments. Finally, the rule required robust community participation in the development of the assessment, ensuring that those most impacted by housing and community development decisions had a voice in the planning process.

HUD accepted Assessments of Fair Housing submitted by forty-one different jurisdictions and saw a clear improvement under this system. Compared to the previous framework, these forty-one jurisdictions were able to produce more precise fair housing goals, metrics, and timelines. They engaged more with community groups, public housing agencies, and even other jurisdictions in the region to create comprehensive fair housing plans. Unfortunately, we cannot know how successful these efforts would have been, as the Trump administration put a halt to the process in 2018.

Now, HUD has proposed a rule to replace the previous guidance. The proposed rule reverses many of the positive aspects of the 2015 rule and, instead of working to affirmatively further fair housing, would likely allow the further entrenchment of patterns of discrimination and segregation. First, the new rule redefines “fair housing choice” as “allowing individuals and families to have the opportunity and options to live where they choose, within their means.” Race and class are deeply intertwined, making the “within their means” language problematic. It introduces class differences as an excuse for jurisdictions to shirk their responsibility to promote racial integration.

Second, the proposed rule abandons the AFH process. The AFH system – and the “Analysis of Impediments” system which came before it – served to guide program participants in their duty to affirmatively further fair housing. The proposed replacement, on the other hand, would allow jurisdictions to shirk this important responsibility. The “AFFH certification” process, as it is known, does not require any community collaboration, nor does it require any data collection or analysis. For the AFFH certification, HUD would only require that a jurisdiction identify three goals and explain how addressing those goals would address fair housing. But even those minimal requirements would be waived if the jurisdiction were to choose its goals from a list of sixteen “obstacles” that HUD considers to be inherent barriers to fair housing choice. The effect of the exemptions is to steer jurisdictions toward choosing the “obstacles,” to minimize their responsibility.

Additionally, the sixteen inherent barriers to fair housing named by HUD do not actually have to do with fair housing. Rather, they are things like design standards, building codes, labor protections, environmental rules, and energy efficiency policies, which might inhibit new construction and, thus, growth of a locality’s housing supply, but do not really pertain to fair housing choice. While housing supply is important, simply increasing the availability of market-rate housing will not necessarily result in housing that is affordable for low-income people, nor will it eliminate discrimination or challenge segregation. Further, many of these “obstacles” are crucial for the protection of people and the environment. Ultimately, the proposed certification process is a thinly veiled push for deregulation that would do little to promote integration and equality.

Finally, under the proposed rule, public housing agencies would essentially be released from their responsibility to affirmatively further fair housing. They would be required to certify that they consulted with local jurisdictions on satisfying shared AFFH obligations, but would not have to provide any analysis of fair housing issues or goals for addressing those issues. Public housing agencies serve millions of Americans, including a significant number of people of color and people with disabilities, so it is crucial that they play a proactive role in advancing fair housing choice.

The AFFH provision of the FHA provided a framework by which we as a nation could begin to right the wrongs of decades of discrimination and segregation. It directed us toward a vision of integration and opportunity for all. HUD’s proposed rule ignores these central purposes, and instead takes a free market approach that simply does not work. At a time when complaints of housing discrimination are rising, with over 31,000 complaints filed in 2018 alone, we cannot trust the free market to ensure fair housing choice. Instead, we must recommit to vigorously combating discrimination, breaking down barriers to opportunity, and building the racially integrated society promised by the FHA over half a century ago. Until we do so, we will continue to see unjust disparities in wealth and wellness, and our nation’s promise of equal opportunity will continue to ring hollow.

HUD’s proposed AFFH rule has not been enacted yet. You can make your voice heard on this important issue by submitting a comment at https://www.fightforhousingjustice.org/affh-comment. The deadline to do so is Monday, March 16, 2020.

———

If you believe you may have experienced discrimination in housing, you can contact the Equal Rights Center. To report your experience, please call 202-234-3062 or email info@equalrightscenter.org.